Aug 18, 2018 • 2364 words

Digital Card Game - Part 1

This is a guide for creating a card game, much like Blizzard’s Hearthstone. I will be creating a new card game in JavaScript and — in a later post — rendering the game with Three.js. If you don’t have any experience with JavaScript and Node.js you might find this guide hard to follow. In that case, I recommend you bookmark this page and go google some introductory tutorials :).

1. Design goals

- Instead of copying Hearthstone verbatim we’re going to keep things a little fresh and switch up the theme. I’ve recently been playing Android: Netrunner, switching to a cyberpunk theme could be fun. Just by switching the theme gives me inspiration for changes to mechanics.

- Instead of Mana there will be CPU. CPU still behaves like Mana: any unspent CPU is removed at the end of the turn. At the start of your turn you regain all your CPU, which grows over the course of the game.

- I’ll introduce a new resource called Memory. Memory is consumed and not refreshed each turn.

- Instead of Minions there will be Programs which cost CPU and Memory.

- When you first play a Program it will be Booting and cannot be used until your next turn.

- Attacks in Hearthstone deal ‘sticky damage’. That is the damage they receive is persisted from turn to turn. Program cards in this game will have a strength and will regain their full strength at the end of a turn. Attacks will also cost CPU.

- All program cards have Taunt. You cannot attack the hero until all opponent programs are defeated. This still leaves the possibility of some programs having a trait that can directly attack the hero.

- I’ll also introduce a new losing condition,

stolenborrowed from Netrunner. When your hero character takes damage they randomly discard cards. If a hero takes damage and has no cards to discard they die and lose the game.

2. Setup the development environment

Before you begin, make sure you have Node installed. https://nodejs.org/en/

Open your terminal in your development directory and run the following:

npx create-react-app cyberpunk-card-game

cd cyberpunk-card-game

I highly recommend VS Code as a text editor. It is a pleasure to use. Once you have it installed you can simply run the following in your terminal to launch VS Code and open the directory:

code .

I’m going to use a framework called boardgame.io. This framework lets me jump in and focus on just logic specific to the card game. It handles players, turns, phases, state management and networking for us.

npm install --save boardgame.io

With that out of the way, we can start writing some logic!

3. Basic logic

I like to keep things simple to start with. Some developers prefer to think about how the ‘architecture’ of the code will be upfront. I prefer to jump right in and implement the basic functionality.

To begin with, I’ll create a move to draw a card. The very first thing I’ll need is an object to store our game’s state in.

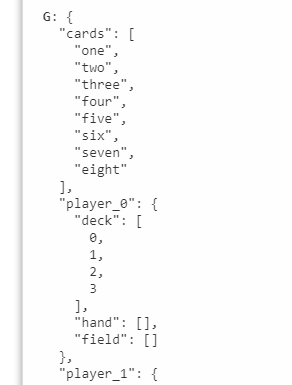

// file: src/GameLogic.js

function initialState() {

return {

cards: ["one", "two", "three", "four", "five", "six", "seven", "eight"],

player_0: {

deck: [0, 1, 2, 3],

hand: [],

field: []

},

player_1: {

deck: [4, 5, 6, 7],

hand: [],

field: []

}

};

}

You will see why I implemented this as a function later on. I want to keep the structure of the state as flat as possible, this makes it much easier to work with. The deck and hand arrays contain the card’s index in the cards array. Next I’ll create the function that draws a card to our hand.

// file: src/GameLogic.js

function drawCard(currentState) {

// TODO: we'll need a way to know which is the current player

// at some point.

// but for now let's assume it's player 0.

let playerID = "player_0";

let player = currentState[playerID];

// Add the last card in the player's deck to their hand.

let deckIndex = player.deck.length - 1;

let hand = [...player.hand, player.deck[deckIndex]];

// Remove the last card in the deck.

let deck = player.deck.slice(0, deckIndex);

// Construct and return a new state object with our changes.

let player = { ...player, hand, deck };

let state = { ...currentState, [playerID]: player };

return state;

}

If you’ve never seen those three dots ... before, that might look confusing. It’s called a rest operator and it performs a shallow copy of the object following it. Anything listed after a rest operator will either be appended to the object or overwrite existing fields, if it has the same name.

Working this way ensures we never mutate the current state. Our functions should always return a new state object. Not only does this make our state changes easier to reason about, it also makes it trivial to implement features such as undo/redo and replays.

We can test this out.

// file: src/GameLogic.js

let state_0 = initialState();

let state_1 = drawCard(state_0);

console.log('state_0', state_0);

console.log('state_1', state_1);

Run it using this command: node src/GameLogic.js

// Output:

state_0 { cards: [ 'one', 'two', 'three', 'four', 'five', 'six', 'seven', 'eight' ],

player_0: { deck: [ 0, 1, 2, 3 ], hand: [], field: [] },

player_1: { deck: [ 4, 5, 6, 7 ], hand: [], field: [] } }

state_1 { cards: [ 'one', 'two', 'three', 'four', 'five', 'six', 'seven', 'eight' ],

player_0: { deck: [ 0, 1, 2 ], hand: [ 3 ], field: [] },

player_1: { deck: [ 4, 5, 6, 7 ], hand: [], field: [] } }

Can you spot the difference between the two states? I will formalise this as an actual test. The initial state will be changing a lot, so let’s add an override:

function initialState(state) {

return state || { //...

and replace the test code at the bottom with an export:

export {initialState, drawCard};

I want my test to assert the following…

graph TB;

a("state at time 0 = {deck: [0,1,2,3], hand: []}")

b["drawCard()"]

c("state at time 1 = {deck: [0,1,2], hand: [3]}")

a-->b

b-->c

// file: src/GameLogic.test.js

import {initialState, drawCard} from './GameLogic';

let mockState = {

cards: ["one", "two", "three", "four", "five", "six", "seven", "eight"],

player_0: {

deck: [0, 1, 2, 3],

hand: [],

field: []

},

player_1: {

deck: [4, 5, 6, 7],

hand: [],

field: []

}

};

// The test function is provided automatically by the

// framework that was installed when we used create-react-app.

test('drawing a card', () => {

let state_0 = initialState(mockState);

let state_1 = drawCard(state_0);

expect(state_0.player_0.deck).toEqual([0, 1, 2, 3]);

expect(state_1.player_0.deck).toEqual([0, 1, 2]);

expect(state_0.player_0.hand).toEqual([]);

expect(state_1.player_0.hand).toEqual([3]);

});

Running tests is easy, just run npm test.

You might be asking, ‘what was the point of downloading that boardgame.io thing?’. I’ll get to that!

3.1 Boardgame.io

In this chapter I’ll get the drawCard function working with boardgame.io. I don’t remember everything about every library I use, so I’m going to head to their website to refresh my memory on how it works: http://boardgame.io/#/tutorial.

First, clear out everything inside src/App.js and replace it with the following:

// file: src/App.js

import { Client } from 'boardgame.io/react';

import { Game } from 'boardgame.io/core';

import {initialState, drawCard} from './GameLogic';

const CyberpunkCardGame = Game({

setup: initialState,

moves: {

drawCard

}

});

const App = Client({

game: CyberpunkCardGame

});

export default App;

Boardgame.io provides us with two functions: Game and Client. Game takes an object where we defines how the state is setup and the list of possible game moves. I simply plug-in my own functions. Client creates the front-end view for us, it comes with a neat debug side-panel.

If you run it, a webpage will automatically open in your browser. npm start.

In the side-bar, the game’s state is listed under G. But wait, that’s not what the state is suppose to look like! Turns out, the setup function expects the first argument to be ctx (short for context). Boardgame.io has an additional state object called ctx and that keeps information such as how many players are in the game, who the current player is, etc.

// file: src/GameLogic.js

// Fix the bug by adding the ctx argument.

function initialState(ctx, state) { //...

The debug side-bar even let’s us activate our moves. Press drawCard and then enter.

The next move to implement is playing a card. Each player has their own ‘field’ array. This represents the part of their table where the player lays down a card. If you are following along, try and implement this function yourself.

// file: src/GameLogic.js

// The currentState and ctx argument is provided by boardgame.io

function playCard(currentState, ctx, cardId) {

let playerID = "player_0";

let currentPlayer = currentState[playerID];

// Find the card in their hand and add it to the field.

let handIndex = currentPlayer.hand.indexOf(cardId);

let field = [...currentPlayer.field, currentPlayer.hand[handIndex]];

// Remove the card from their hand.

let hand = [...currentPlayer.hand.slice(0, handIndex), ...currentPlayer.hand.slice(handIndex+1)];

// Construct and return a new state object with our changes.

let player = {...currentPlayer, hand, field};

let state = {...currentState, [playerID]: player};

return state;

}

export {initialState, drawCard, playCard};

3.2 Refactoring

I am already starting to repeat myself, there’s similar code between drawCard and playCard. Also, the line where I remove the card from their hand is a little too verbose for me. I’d prefer a set of functions for dealing with arrays in an immutable fashion. Also, let’s fix always using player 0.

I prefer to write the use-case code first, even if the functions don’t exist yet.

// file: src/GameLogic.js

function drawCard(currentState, ctx) {

let {currentPlayer, playerId} = getCurrentPlayer(currentState, ctx);

// Add the last card in the player's deck to their hand.

let deckIndex = currentPlayer.deck.length - 1;

let hand = ImmutableArray.append(currentPlayer.hand, currentPlayer.deck[deckIndex]);

// Remove the last card in the deck.

let deck = ImmutableArray.removeAt(currentPlayer.deck, deckIndex);

// Construct and return a new state object with our changes.

return constructStateForPlayer(currentState, playerId, {hand, deck});

}

function playCard(currentState, ctx, cardId) {

let {currentPlayer, playerId} = getCurrentPlayer(currentState, ctx);

// Find the card in their hand and add it to the field.

let handIndex = currentPlayer.hand.indexOf(cardId);

let field = ImmutableArray.append(currentPlayer.field, currentPlayer.hand[handIndex]);

// Remove the card from their hand.

let hand = ImmutableArray.removeAt(currentPlayer.hand, handIndex);

// Construct and return a new state object with our changes.

return constructStateForPlayer(currentState, playerId, {hand, field});

}

It’s a rapid way of working. Now I know exactly which functions I need to implement.

// file: src/GameLogic.js

function getCurrentPlayer(state, ctx) {

let playerId = "player_" + ctx.currentPlayer;

let currentPlayer = state[playerId];

return {currentPlayer, playerId};

}

function constructStateForPlayer(currentState, playerId, playerState) {

let newPlayerState = Object.assign({}, currentState[playerId], playerState);

return {...currentState, [playerId]: newPlayerState};

}

const ImmutableArray = {

append(arr, value) {

return [...arr, value];

},

removeAt(arr, index) {

return [...arr.slice(0, index), ...arr.slice(index + 1)];

}

};

a quick aside

I have tried different paradigms of programming over the years. A common one is object orientated programming, which forces you to group data and logic into ‘Objects’. I have come to find my favourite way of programming is starting with simple functions, refactoring as I go along. Casey Muratori calls this ‘Compression Orientated Programming’. https://caseymuratori.com/blog_0015

“I look at programming as having essentially two parts: figuring out what the processor actually needs to do to get something done, and then figuring out the most efficient way to express that in the language I’m using.” — Casey Muratori

I will add a test for playCard, and the test for drawCard will need updating, as our moves now require the context object.

// file: src/GameLogic.test.js

test('drawing a card', () => {

let state_0 = initialState(mockCtx, mockState);

let state_1 = drawCard(state_0, mockCtx); //...

test('playing a card', () => {

let state_0 = initialState(mockCtx, mockState);

let state_1 = drawCard(state_0, mockCtx);

let state_2 = playCard(state_1, mockCtx, 3);

expect(state_1.player_0.field).toEqual([]);

expect(state_1.player_0.hand).toEqual([3]);

expect(state_2.player_0.field).toEqual([3]);

expect(state_2.player_0.hand).toEqual([]);

});

All test pass.

In the next part of this series, I’ll handle CPU and Memory resources as well as Attack moves.